Factors that contribute to test anxiety

Students who have higher general trait anxiety (an aspect of personality) tend to be more likely to have test anxiety. The overall anxiety in students' lives can carry over into other aspects of their lives, such as testing.

During an ongoing period of uncertainty, such as the recent pandemic, an increase in general worry can lead to an increase in test-related anxiety. Because tests often have a lower locus of control for students than other assessments, they are more likely to be identified as a threat. Remember, problematic worry demands certainty and control.

Students with perfectionist tendencies also tend to have higher rates of test anxiety, since they set high-performance standards that may not be achievable. They also tend to connect their self-worth to meeting these goals (e.g., Vanstone & Hicks, 2019).

Test anxiety rates are often higher amongst students who feel they do not belong in the classroom. For example, women in STEM courses report higher levels of test anxiety than their male colleagues (e.g., Samuel & Warner, 2021). When students feel a sense of belonging in the classroom, they report lower levels of test anxiety within their classroom environment. For example, Loose & Vasquez-Echeverría (2021) found that first-generation and/or racialized students reported lower test anxiety and increased motivation when they felt like they belonged in the classroom.

As a form of situational anxiety, test anxiety is directly influenced by the learning environment. This includes the classroom, the department, and the university as a whole. Several aspects of the assessment design can impact threat perceptions.

-

In the classroom

Students who are provided opportunities to process information through active learning are less likely to perceive tests as a threat. This learning helps students feel prepared and be more resilient during these challenges (Cardozo et al., 2020). This could be because students feel they can meet the performance objectives, which can reduce perceptions of tests as threats.

-

In the department

Departments that emphasize ranking and competitiveness can create a test-conscious environment. In a test-conscious environment, students are more likely to emphasize test performance over learning goals. As a result, students are more likely to perceive tests as a threat.

-

In the university as a whole

Midterms and final exams tend to occur at the same time across various courses. Having multiple exams over a few days increases students’ perception of tests as threats. Students are more likely to perceive tests as threats if they feel that they do not have sufficient time to prepare for the assessments.

Reflection:

An ecological perspective on test anxiety looks beyond the individual to understand what triggers anxiety. Using this approach, you can consider the culture of testing in your discipline and/or department.

If someone were to look at your department as a whole, would it be perceived as test-conscious? Are there practices in place that emphasize test performance, rather than learning outcomes?

Test anxiety goes beyond the test

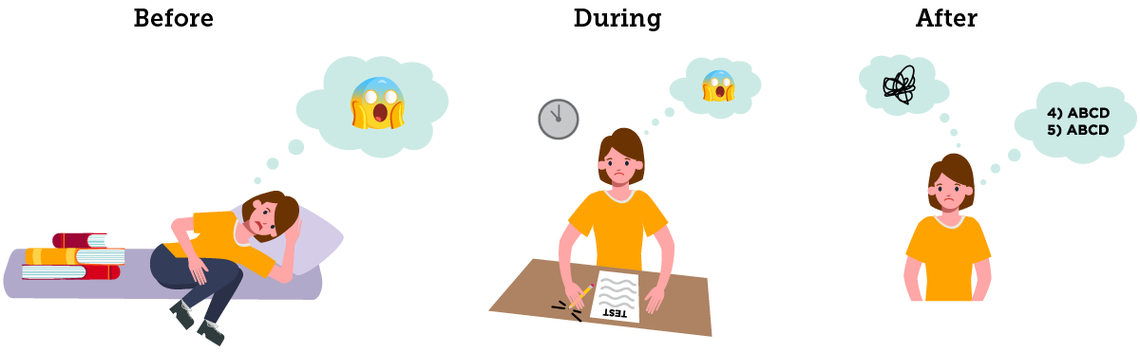

Typically, test anxiety is associated with the testing event; however, the impact of test anxiety can shape all points where students think about a test, including before and afterwards. Students’ perception of tests as threat effect how they prepare for them and reflect on their results. When tests are perceived as a threat, students may engage in maladaptive behaviours to cope with the feeling of uncertainty at any point prior, during, and after the test.

Before the test: Test anxiety’s impact on the study behaviour

Test anxiety can be triggered before the exam, such as when students are preparing for the exam. This pre-test anxiety may last longer, such as over a series of weeks, in comparison to the anxiety felt while writing a test. As such, they may engage in maladaptive behaviour before the exam to cope with the uncertainty.

Because of the negative impact of anxiety, students may delay study behaviour to avoid the feeling. Students may also withdraw effort from studying if they believe they cannot meet their performance objectives (Barutçu Yıldırım & Demir, 2020). By withdrawing effort, students can save face and attribute poor performance to their lack of preparation.

Text anxiety can also impact students' use of study strategies and the quality of their study practices. Many students with perfectionist tendencies may spend large amounts of time studying for tests, but use ineffective approaches. During this excessive studying, students are more likely to make mistakes or affirm misunderstandings and have reduced concentration (Shadach et al., 2017). Others note that worry can interfere with the study process, impeding the students’ ability to store and organize content in their memory.

When students perceive a test as a threat, students may seek out as much information as possible about the test to reduce the feelings of uncertainty (Huntley et al., 2016). This information seeking becomes a coping response, where students ask about specific content and questions on the exam. In contrast, some students will avoid discussion about the exams or asking questions altogether, fearing negative judgement.

During the test: Test anxiety’s impact on test writing behaviour

Because of the increased arousal in the anxiety response, students experiencing test anxiety may be more fidgety during their test. The sympathetic nervous system response can make it harder to sit still. You might notice increased eye movement or more requests to use the washroom. Some instructors may misconstrue these behaviours as a signal of misconduct. It is helpful to gather more information about what the student is experiencing first.

To cope with the uncertainty, students may engage in rituals or habits that can give them a sense of control. This can include needing to write the exam in a particular location, accessing lucky charms, or wearing specific clothing.

Another way that students may cope with uncertainty during test writing is to look for reassurance, often by asking several clarifying questions (Bledsoe & Baskin, 2014). Students will ask questions to help compensate for a lower tolerance of confusion and ambiguity. With a low tolerance for error, students with test anxiety may pose questions that are confirming the correctness of their responses.

After the test: Ruminations on performance

Test anxiety also impacts how students respond to their test results and the feedback that it provides for their learning.

Test anxiety can linger after the test and shape how the student reflects on the experience. In particular, students may engage in ongoing thinking about the test and recall negative aspects (Woodgate et al., 2020). Students may overgeneralize their mistakes or failure, but selectively recall the question that they feel they did poorly on. This often serves to reaffirm their perception that the test was a threat.

When a test is perceived as a threat, students who perform successfully on the test attribute their strong result to luck and not to their study behaviours. In contrast, when students perform poorly, they attribute failure as a statement of their current and future ability (Numan & Hasan, 2017) to be successful.

Reflection:

Reflect on your teaching experience. What examples of the behaviour described above have you encountered? How did you first interpret these behaviours? How does your interpretation of the behaviours change when attributing them to coping with anxiety? How might the above information about test anxiety change your response to a student?

By understanding test anxiety as a reoccurring emotional response to uncurtaining, instructors can understand how the anxiety can be viewed as a product of the learning environment and not just individual traits. Like fear, test anxiety is triggered by perceiving the test as a threat; unlike fear, test-anxiety can’t be resolved as the uncertainty remains. Understanding how test anxiety is triggered and expressed will help instructors respond with compassion

Lesson checklist

After this lesson, you will be able to:

-

Distinguish between anxiety and fear

-

Differentiate between test anxiety, trait anxiety and stress

-

Explain how anxiety impacts attention, decision-making and memory

References

Barutçu Yıldırım, F., & Demir, A. (2020). Self-handicapping among university students: The role of procrastination, test anxiety, self-esteem, and self-compassion. Psychological Reports, 123(3), 825–843. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118825099

Bledsoe, T. S., & Baskin, J. J. (2014). Recognizing student fear: The elephant in the classroom. College Teaching, 62(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2013.831022

Cardozo, L. T., Azevedo, M. A. R. de, Carvalho, M. S. M., Costa, R., de Lima, P. O., & Marcondes, F. K. (2020). Effect of an active learning methodology combined with formative assessments on performance, test anxiety, and stress of university students. Advances in Physiology Education, 44(4), 744–751. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00075.2020

Huntley, C. D., Young, B., Jha, V., & Fisher, P. L. (2016). The efficacy of interventions for test anxiety in university students: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Educational Research, 77, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.03.001

Loose, T., & Vasquez-Echeverría, A. (2021). Academic performance and feelings of belonging: Indirect effects of time perspective through motivational processes. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01779-4

Numan, A., & Hasan, S. (2017). Test-anxiety-provoking stimuli among undergraduate students. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 27(1).

Samuel, T. S., & Warner, J. (2021). “I Can Math!”: Reducing math anxiety and increasing math self-efficacy using a mindfulness and growth mindset-based intervention in first-year students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 45(3), 205–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2019.1666063

Schillinger, F. L., Mosbacher, J. A., Brunner, C., Vogel, S. E., & Grabner, R. H. (2021). Revisiting the role of worries in explaining the link between test anxiety and test performance. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1887–1906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09601-0

Shadach, E., Levy-Frank, I., Levy, S., Shadach, E., & Amitai, T. (2017). Preparatory test anxiety: Cognitive, emotionality, and behavior components. Studia Psychologica, 59(4), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.21909/sp.2017.04.747

Vanstone, D. M., & Hicks, R. E. (2019). Transitioning to university: Coping styles as mediators between adaptive-maladaptive perfectionism and test anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.12.026

Woodgate, R., Gonzalez, M., Stewart, D., Tennent, P., & Wener, P. (2020). A socio-ecological perspective on anxiety among Canadian university students. Canadian Journal of Counselling of Psychotherapy, 54(3), 485–519.